I often bring a quote from another author to the research guys and ask for their opinion. While reading Bristol-Rhys and Osella’s chapter on “Gendered and Sexual Stereotypes in Abu Dhabi” (2016, full cite below) I was struck by how their informants tied the definition of masculinity to clothing:

We turned first to masculinity as it is measured and judged by Emirati men. Through interviews and discussions with Emirati men from 18 to 65 years old, it became clear that physical presentation was paramount. How a man presents in public is key; he must be in national dress and it must be perfect.

I wondered how the research guys would define what were the qualities of a man so during a picnic dinner, I asked if I could throw out a question and record (by writing) their answers. The six men (from six different tribes) agreed. Since I didn’t know how Bristol-Rhys and Osella framed their questions, I started with “What can you tell about a man by looking at him? Can you tell if a man is good by looking at him?” And the unanimous reaction was “you can’t know from the first time.” It was impossible to tell if a man was good by seeing him, one has to talk to a man to recognize what he is.

The consensus was that best quality of a man is that he is ethical/ moral (athlaq) and one can’t know that without a lot of interactions. As one man said, “I was told that to know a man you must trade with him or travel with him or live next to him.” Thus, by being in business (buying or selling something), going on a long trip or being neighbors you will see a man in enough different situations to come to an understanding of his personality. [To me, this is the Omani equivalent of the Maya Angelou quote: “I’ve learned that you can tell a lot about a person by the way they handle a rainy day, lost luggage, and tangled Christmas tree lights.”]

Then picking up on Bristol-Rhys and Osella’s discussion of behavior in the majlis (full quote below), I asked about how one could tell if a man was good or not from seeing him in a majlis. Again the unanimous decision was that one cannot know from his “talk in the majlis, maybe his talk is good but he is not.” You should “check his speech,” but it’s more important to pay attention to what he does. Specific points about how a good man acts include:

- When others speak, he listens carefully and listens to all equally (i.e. not paying attention to men who are sitting close to him or have special status while ignoring others) [One man made the particular point that one cannot judge a man in his own house the same way, as in his own majlis a man has “his homework,” i.e. being generous, making sure there is enough tea and food so he might not be able to follow the conversation/ respond as carefully]

- Speaks, but not too much, i.e. not dominating all the conversation

- Does not try to give special greetings/ try to sit next to important men but treats all men equally [this point was illustrated by one of the men acting out how a groveling/ fawning man behaves]

- Does not interrupt others

- Does not talk badly about others

- Does not show jealousy or anger

- Never boasts

- Never exaggerates

- Never contradicts or corrects an older man, even if the older man is saying things that aren’t true or is speaking badly

- If he stands up to get himself tea or water, he is happy to give to everyone (even younger men!); passes food and drinks; acts hospitable

- Sits up straight (not slouching)

When we finished talked about behavior in the majlis, one of the man stated, “If someone you trust says a man is good, then one should listen [i.e. take it under advisement] but you have to check for yourself.”

Another man added that you can sometimes tell a good man by his talk when he makes statements about his actions. For example, a man is good if his conversation includes statements such as “I will” or “I did”:

- visit this person who is sick

- visit this person in the hospital

- go to this person’s funeral

- go to this person’s wedding

When I asked, “in general, if there is a man who have met a few times, so you know him but not every well, how can you learn if he is a good man or not?” all the answers hinged on seeing proper behavior such as:

- Greeting all people

- Helping all people (for example if a stranger has a flat tire – another man chimed in and said “a good man will help you from the first time,” meaning both ‘even if he doesn’t know you’ and ‘will help without you having to ask twice’)

- Being generous (for example bringing food or drinks when meeting friends for a picnic)

- Treating waiters/ people who work in stores politely

- Being kind to children

- Having patience (for example if the food is served late in a restaurant)

- Doing the work/ doing extra work so that older people can “sit and take their rest”

- Helping the members of their tribe (staying connected socially to people such as helping others when they are sick, going to social events of family members, etc.

One example that I thought was very interesting was one man said specifically, that a good man respects his religion and the religion of others. He gave the example that a good man knows his own religion, i.e. if he is a Muslim, then he should know to pray 5 times a day at the time of prayer.

As the conversation was winding down, three more points were raised. One man said, “a good man has a good heart, he will forgive quickly. If someone says something bad, he will smile and answer quietly.” He continued, “if there is a hard discussion, he will greet you the same the next day.”

Another man said, “a good man will not speak of [meaning “make fun of”] your clothes or your car.” And the last comment was, “a good man is always good with his family.”

As there were no more remarks, I paraphrased Bristol-Rhys and Osella’s conclusions and their reaction was a flat “no.” In his own way, each man expressed disagreement from a head shake to “we do not agree,” “not clothes!” and “we do not think like that.” No one expounded on his beliefs; they did not agree with the opinions of the Emirati men, but they did not feel that they needed to explain their disagreement in detail. I put away my research book and the topic turned to another subject.

I discuss this conversation further in: Ethnography: Conversations about Men/ Masculinity, part 2

Bristol-Rhys, Jane and Caroline Osella. 2016. “Neutralized Bachelors, Infantilized Arabs: Between Migrant and Host Gendered and Sexual Stereotypes in Abu Dhabi,” in Masculinities Under Neoliberalism. Andrea Cornwall, Frank G. Karioris and Nancy Lindisfarne, eds. London: Zed.

(underlining – my emphasis)

We turned first to masculinity as it is measured and judged by Emirati men. Through interviews and discussions with Emirati men from 18 to 65 years old, it became clear that physical presentation was paramount. How a man presents in public is key; he must be in national dress and it must be perfect. An Emirati man’s kandoura must be immaculate and, unless in winter, it should be gleaming white. His gutra and agal must be worn correctly and he should not “fiddle” with it as if it were an unusual accessory. A beard is mandatory and it should be trimmed perfectly (in fact, we were told that a man should have his beard trimmed “professionally” at least 3 times a week) What a man wears on his feet is important as well and it is unacceptable to wear trainers or sports sandals. There are several acceptable styles, – even Birkenstocks are considered ‘aady (normal) – but the sandals should be white leather in summer. During winter, darker sandals are acceptable and, if wearing a western style sport coat over a kandoura, then loafers or brogues, worn with socks, are also appropriate. This critical scrutiny of attire might indicate the success of the nationalist project of Emirati, indeed Khaleeji, dress (cf. Al Qasimi 2010); it was the importance placed on the “correct kandoura” and the “correct sandals” and the “proper way of wearing the gutra and agal” that was emphasized, stressing the cultural competence necessary to negotiate the performative demands of “correctness.”

Cultural competence was stressed again and again throughout our interviews with Emirati men. “A man recognizes a man by how he enters the majlis,” said one of our interlocutors. Another man listed carefully the behaviors that are noticed and noted in a majlis. “We watch how a person enters and then greets the people in the majlis. Does he know whom to greet first? Does he recognize those men like the sheikh of his tribe, younger sheikhs of the ruling family, and the men who are important to his father and uncles?” In addition to knowing who is who, and the order in which important men must be greeted, the greeting itself was also critically assessed. “Does the man use the correct religious phrases in his greetings? Does he know when to touch noses (ywayeh) and when to only shake hands?” And a man’s knowledge of his society is judged as well. “In conversation with the men in attendance at the majlis, does he know his tribal history and lineage? Does he know how his tribe connects – or not – to the other tribes? All these things must be known well for a man to be thought a man.” All of these behaviors require knowledge – gendered, culturally specific, and highlight exclusive knowledge – in order to perform them adequately.

Outside of the majlis, in more informal situations and in the public spheres of malls and universities, we learned that a man is measured by how he acts, by those with whom he is seen to associate with in public. According to our Emirati interlocutors, clothing is still important in public spaces because there they are judged not only by Emiratis, but also by foreigners. “We must dress and act appropriately in public because of the image, the image of the Emirati man.”

The young men at the university where Bristol-Rhys teaches have a hierarchy of dress with which they judge each other and establish boundaries between cliques of friends. First, there are the men who wear only kandoura and gutra/agal to classes. They describe themselves as “pure Emirati men”. Then there are those who wear kandoura with an American baseball cap or nothing at all on their head – these are considered “okay Emirati, but too casual” and comments / assumptions usually follow fast that, “their mother is not Emirati.” The third group is made up of those who wear jeans, t-shirts, and shorts to university; they are scorned by the “pure Emirati” and are only grudgingly accepted by the group who wear baseball caps. They describe themselves as “trendy,” but others use words such as “fake, wannabe American, or zaalamat, the pejorative term for Levantine Arabs, that has, for lack of a better term, sleazy connotations in Emirati society. “They try too hard to be seen, and that is not the Emirati way. We are always supposed to be at ease, we don’t show anxiety, in fact, the best is if you can look bored.”

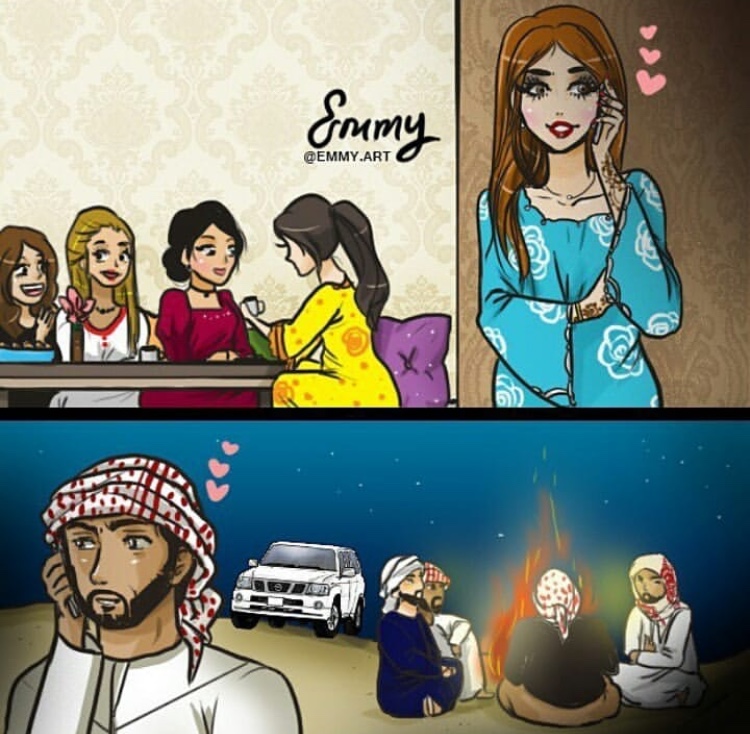

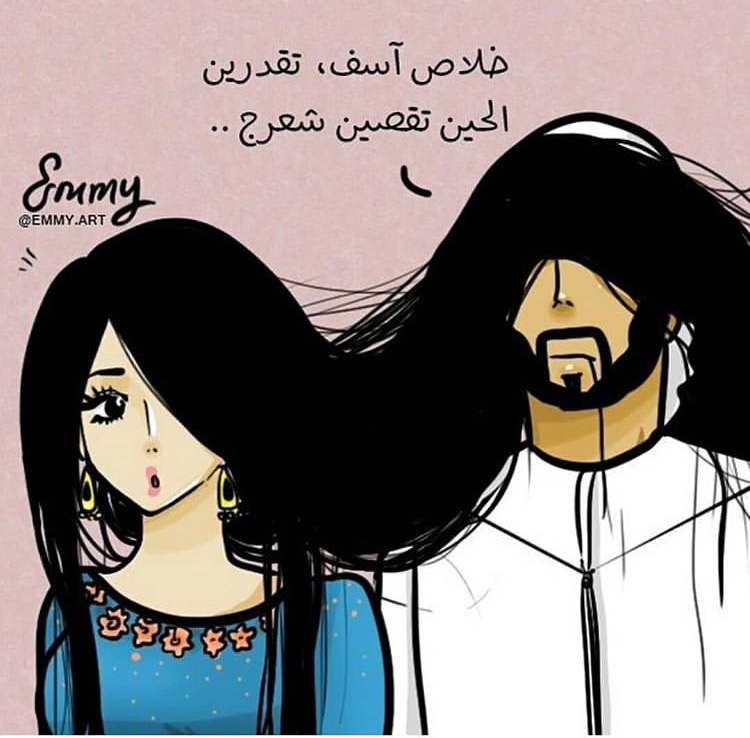

It’s not my area of expertise, but I find relationship cartoons posted on social media fascinating. There is so much cultural information to be unpacked for example, many have women with uncovered hair in settings with other women, whereas Dhofari women keep their hair covered even if sitting in the salle with other women. Here are a few I find particularly interesting. I hope someone from or living on the Arabian Peninsula does some kind of systematic study by country, topic, etc.

It’s not my area of expertise, but I find relationship cartoons posted on social media fascinating. There is so much cultural information to be unpacked for example, many have women with uncovered hair in settings with other women, whereas Dhofari women keep their hair covered even if sitting in the salle with other women. Here are a few I find particularly interesting. I hope someone from or living on the Arabian Peninsula does some kind of systematic study by country, topic, etc.

You must be logged in to post a comment.