I am grateful to A. Jaboob for allowing me to post these beautiful photos of the Dhofar mountains in khareef.

I am grateful to A. Jaboob for allowing me to post these beautiful photos of the Dhofar mountains in khareef.

I am grateful to W. Jaboob for allowing me to post these beautiful photos of the Dhofar mountains in khareef.

I am happy to announce that my third book, Houseways in Southern Oman, is now available for pre-order

https://www.routledge.com/Houseways-in-Southern-Oman/Risse/p/book/9781032218595

https://www.amazon.com/Houseways-Southern-Oman-Marielle-Risse/dp/1032218592

https://www.amazon.com/Marielle-Risse/e/B08SKYD848/ref=dp_byline_cont_pop_book_1

(photo by Salwa Hubais)

Given the current upheaval about what women wear, I am re-publishing an essay I wrote 5 years ago: Living Expat – Dressing, Covering, Swimming, and Mutual Respect

I have read several essays about supporting women’s right to not wear headscarves/ modest clothing. I wish the argument was framed a little differently and centered on women’s right to CHOOSE what they want to wear.

I have lived in Oman on the Arabian Peninsula for 17 years and I have never been harassed, insulted, frightened, much less attacked, by any Omani for being American or a Christian. Likewise, I have never been made to feel different or foreign or wrong because I was wearing clothes which were normal in my culture. Because I choose to live and work here, I do make the small adjustment of wearing clothes that cover my knees and shoulders when teaching, but I wear the same brands I wear when I’m in the States: Jjill, Fresh Produce, LL Bean, Eddie Bauer and April Cornell.

When I visit Omani friends at home, I wear what they are wearing out of respect. It is a simple adaptation like taking off my shoes before I walk into a friend’s house and learning to eat with my hands, as in the States I would shooing my cats out of the living room if a friend who is allergic comes to visit or not eating ice cream sundaes in front of a friend who is dieting.

In Omani houses, I wear an abayah (the long loose black cloak that women wear on the Arabian Peninsula) with a black headscarf or a dhobe (the long, loose, patterned cotton dress local women wear) with a lossi (a matching, light cotton headscarf). At first it was a little difficult to maneuver surrounded by almost 4 yards of fabric, but I learned how to gather up some of the extra while walking up stairs and to arrange my lossi to stay neatly in place, something akin to learning to French-braid my hair in middle school.

During Ramadan, I also wore a headscarf during the day out of respect for the culture and I was interested to see how it would feel psychologically to cover. In Oman, unlike some Muslim countries like Saudi Arabia, abayahs and headscarves are not required by law for daily life. Most women wear them because of personal beliefs and/ or traditions. Most women wear abayahs but some are very loose and plain black, some are black have colored decorations, some are colored and some are worn like an open cloak showing the jeans or skirts worn underneath. Some women wear tightly wrapped, plain black scarves, others wear colored scarves or have the scarf resting on their shoulders. Some women (both expat and Omani) have suggested that non-Muslim women should wear headscarves as a show of solidarity. Other women (both expat and Omani) have emphatically told me that I should not wear an abayah as it is not in my heritage.

The first time walking into the mall with a colored headscarf was tough – I felt self-conscious and hypocritical. I am in the mall usually once a week, reading at my café or shopping, and to walk in with a headscarf made me feel like I was playing a game.

When the Omani men in my research group saw me wearing a headscarf for the first time, they would smile, nod, make a quick comment and then ignore the issue; no one ever pressed me to wear a black sheila (headscarf) or abayah. It probably took me six or seven times wearing the headscarf in public until I became comfortable with it; then the only issues were finding scarves which co-ordinated with my clothes and were the right fabric weight, not too heavy or stiff.

My big insight about wearing a headscarf is that it gives you something to do. Standing in the grocery store trying to decide which spaghetti sauce to buy, I reach up, tighten, adjust, and smooth it down. Fussing with the scarf became a habit, a micro-control fidget, like men straightening their tie or shooting their cuffs. It’s a little uncomfortable when it’s hot and humid outside, but very helpful when I’m in a room with the AC on full blast. It’s another 2 minutes of getting ready time as I pull out my tiered hanger with 15 scarves and try to figure out which one looks best with my outfit.

When Ramadan ended, I went back to uncovered hair during the day but I still wear scarves when I see my Omani female friends at home. The result was I put a piece of fabric on my head and it was sometimes a little hot but that’s about it. I did not feel more religious, or less religious, or any particular change. I am a Methodist by baptism and by my own choice when I was in my 20s. Neither my religious devotion or personal beliefs are diminished or altered by having a piece of fabric on my head. I didn’t feel closer to God – I didn’t feel farther away from God. And I don’t believe God enjoins me to judge other people by what they have on their head or their body.

Most Sunday and Tuesday nights I go swimming with 60 or so Arab, Muslim women wearing burqinis. I first learned to swim in a public pool with a Red Cross instructor and over my 50 years I have swum in the Wilde Lake village center pool in Columbia MD, the Old Red Gym at University of Wisconsin-Madison, the University of North Dakota pool when it was negative 10 outside, Canadian lakes, the student center at MIT, the Atlantic Ocean at Ocean City, and the municipal pool in Tacoma, WA.

The women who swim at my pool now are just like the women I have swum with at all those other places, only they are wearing a bit more clothing. They are in swimming pants or leggings with short or long-sleeved tops as is consistent with the conservative culture, but no one has ever told me that I have to wear what they wear. I am a life-long feminist but I don’t believe my feminism allows me to dictate someone else’s feminism. The women at the pool and my Omani women friends (college-educated, multi-lingual, who work and have traveled/ lived abroad) don’t feel comfortable exposing their body to other women, much less men. Who am I to argue that with them?

When I go swimming, I get lots of smiles, waves, friendly glances and “hellos” from women I don’t know. In almost a year of twice weekly visits to the pool I have never received a harsh word, much less a lecture, on my bright blue Land’s End swimsuit. We all exercise mutual respect for different customs and religions while we exercise our bodies. And then we will go home happy. It’s not difficult.

There is a profound joy in introducing students to classic texts. I am very grateful that I have spent so much of my working life among the splendors of ancient Greek plays, Romantic Era poets, Jane Austen and Oscar Wilde.

And I am happy that as I teach I have gotten better at choosing classics which speak to my students, from 20th century writers such as Tawfiq al-Hakim to more modern writers such as Mohammed Al Murr and Badriyah al Bashar. And it’s fun help them get over the newness of Moushegh Ishkhan, Oriah Mountain Dreamer, Ryszard Krynicki, T’ao Yuan Ming, Tomas Tranströmer and Wisława Szymborska.

When I start the poetry class, I know that there is at least one student will be blown away by the Cold Mountain poems, Basho, Mary Oliver, Naomi Shihab Nye or Fowziyah Abu-Khalid. Someone will fall in love with “Embroidered Memory” by Lorene Zarou-Zouzounis; someone else will champion “About Mount Uludag” by Nazim Hikmet.

It’s a delight to read familiar lines and see how students relate to familiar characters. Who is going to defend Ismene this semester? Who will argue on Creon’s behalf? Who is going to laugh when Patty in Quality Street talks about her hopefulness? If we read Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier, who will my students pick as the one who deserves Chris – Kitty, Margaret or Jenny?

At the same time, it is good for me to be in the position of not knowing, to remember how it feels to be confused by a text. I became a better teacher after I spent two summers studying Arabic in Muscat. Sitting in a classroom as a student, panicking when a teacher asked me a question I did not understand, studying for a test and waiting anxiously for my grade made me more understanding of my own students.

So I try to seek out new texts to read and, perhaps, use for teaching. I scan shelves in bookstores and ask friends for suggestions. Since I don’t know Spanish writers, I asked a friend who has expertise and, following her suggestions, found “Marta Alvarado, History Professor” by Marjorie Agosín and “New Clothes” by Julia Alvarez, as well as “Tula” and “Turtle Came to See Me” by Margarita Engle.

Over the past few years, I have realized that I few students are into K-pop (BTS! Blackpink! Twice! NCT!) and so I decided to dip a toe into that cultural tradition.

The easiest way to start was movies so I duly looked at “top 10 Korean movie” lists and rented The Man from Nowhere (2010). One review mentioned that it was similar to Léon: The Professional (1994) in that it involved a young girl who is taken in and protected by a hired assassin. I thought knowing the plot would help me but there were a lot of differences, making the movie both interesting and confusing. For example, the ending surprised me. At the end of Léon, the girl is re-enrolled at her boarding school and she finally plants the small tree that she has been carrying around with her, symbolizing that she is now rooted.

At the end of The Man from Nowhere, the anti-hero asks the police for one favor and he brings the young girl he has been trying to protect back to her old neighborhood, goes into a small convenience store and buys her some composition books, writing supplies and a back-pack. Then he asks her if she will be ok. She nods, they hug and then he turns to go back into the police car.

I stared at the screen in astonishment. “That’s the end?!?” I wondered. Her father left long ago, her mother died at the start of the film, the girl was kidnapped and brutally treated for weeks, and now, with a few stationary supplies, the girl is now alone and supposed to take care of herself?

Over the next few weeks, I watched a few more and was astounded by whole new levels of plotting. It often feels like I am watching several movies at one: Assassination (2015) has freedoms fighters betrayed by team members (shades of Guns of Navarone), funny but doomed killers (shades of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) and twin sisters on opposite sides of an immense cultural, educational and temperamental divide (a grown-up, super spy equivalent of the Parent Trap).

I am often bewildered as I try out comedies, historical fiction and modern thrillers such as The Good, the Bad, the Weird (2008), Masquerade (2012), The Villainess (2017) and War of the Arrows (2011).

It takes a lot of concentration to understand each movie, not because of the sub-titles but the work of trying to create new templates and figure out new tropes. How can I visually tell the difference between good guys and bad guys? Is the behavior of this woman showing that she is good or bad? Does this style of house indicate that the owners are rich, poor, old-fashioned or trend-setters? Is the meal the characters being served haute cuisine or everyday fare? Is this behavior normal or odd?

Sometimes it is good to be lost.

التقاليد المتبعة في ترتيب المنازل بظفار: وضع الأثاث وعلاقته بمجال النظر

click here to see original post: Houseways in Dhofar: Placement of Furniture and Sightlines

I am very grateful to Arooba Al Mashikhi for her work in translating some of my essays about houses in Dhofar.

I am grateful to Maria Cristina Hidalgo [https://www.mariacristinah.com/ ] for her helpful plans and to my informants who have allowed me to chart their homes.

ممتنة لماريا كريستينا هيدالجو لسماحها لي بالاطلاع على خططها المفيدة، -ولأولئك الذين سمحوا لي برسم منازلهم.

[https://www.mariacristinah.com/]

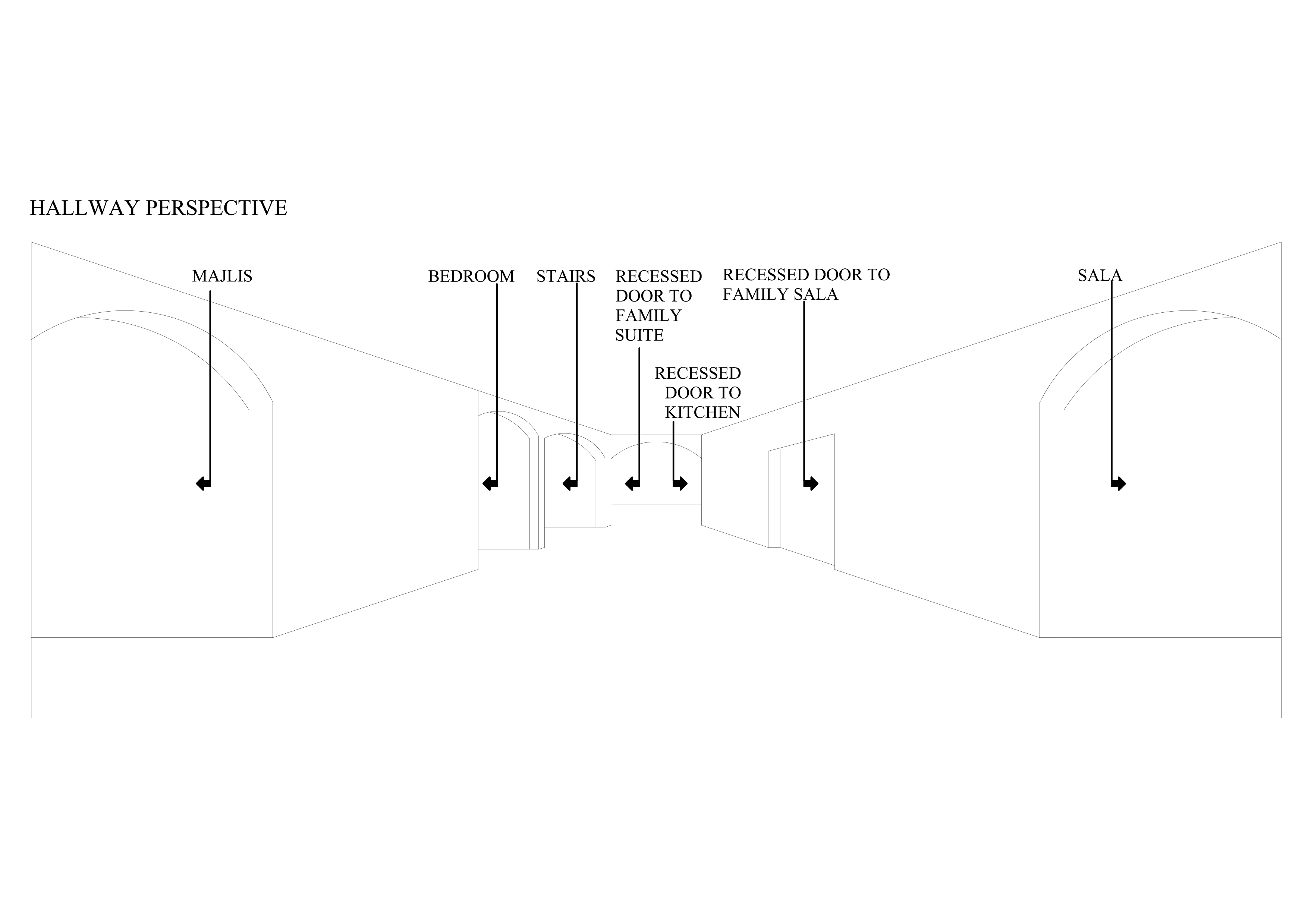

1) Perspective view of front hallway

The first point is that when one walks through the main door, there is often no furniture in sight. Sometimes there is a high, narrow table near the door to set things on that will be out of reach of children or one might be able to get a glimpse into the salle but, as the perspective below illustrates, most of the furnishings are out of sight.

1 – عرض منظوري – للردهة – الأمامية

النقطة الأولى هي أنه عندما يمر المرء عبر الباب الرئيسي، – لا يجدُ في الغالب اثاثاً. -–توجد أحياناً طاولة مرتفعة وضيقة بالقرب من الباب لوضع أشياءٍ وإبقاءها – بعيدًا عن متناول الأطفال أو قد يتمكن المرء من إلقاء نظرة خاطفة على الصالة ولكن ، كما يوضح المنظور أدناه ، فإن معظم قطع الأثاث تبقى بعيدة عن الأنظار -.

2) Ground floor plan with furniture

Below is a bird’s eye view of the same house, showing how, as is usual in Dhofari houses, all the furniture is placed against the wall except for the small, moveable tables in the salle and majlis which are put in front of guests (represented here with small squares).

2) مخطط الطابق الأرضي مع الأثاث

نجدُ أدناه منظراً من الأعلى لنفس المنزل ، يوضح كيف يتم وضع الأثاث كما هو معتاد في المنازل الظفارية ، حيث توضع جميع قطع الأثاث – بمحاذاة الحائط باستثناء الطاولات الصغيرة المتحركة في الصالة والمجلس والتي توضع أمام الضيوف (- ممثلةً هنا بمربعات صغيرة)

A few notes about the ground floor plan:

بعض الملاحظات – عن مخطط الطابق الأرضي:

توضع جميع قطع الأثاث – بمحاذاة الحائط ، وتوضع أبرز قطع الاثاث في المطبخ الذي يحتوي على طاولة صغيرة مدمجة – في الجدار.

– الصالة مفتوحة على – الردهة الرئيسية ولكن يوجد أيضًا باب منزَلِق في الصالة العائلية وباب في المطبخ بالإضافة إلى الباب الخارجي في المجلس. وبالتالي ، يمكن أن يكون هناك أربعة أنواع مختلفة من زوار المنزل في نفس الوقت لا يرى بعضهم البعض الآخر لأن كلاً منهم كان يستخدم بابًا مختلفًا: الضيوف الذكور في المجلس ، و الضيوف الاناث في الصالة والأقارب في صالة العائلة، وعامل تنظيف او تصليح أوشخصا لجلب – الاحتياجات مثل مياة الشرب واسطوانة الغاز – إلى المطبخ.

– يفصل القوس – الذي يعلو نهاية الردهة؛ المنطقة العامة (صالة الضيوف والعائلة) عن المناطق المخصصة للعائلة فقط مثل المطبخ وأحد الأجنحة العائلية

– – تُركّبُ أبواب غرف النوم وغرفة العاملة المنزلية – بزاوية 180 درجة – عن – من يدخل من الباب الأمامي حتى لا يتم رؤية مابداخلها “بالصدفة”. علاوة على ذلك ، – توضعُ الأسرة بطريقة لا يمكن رؤيتها إلا – مِمَّن يدخلُ إلى الغرفة.

– هناك حركة هواء – مستمرة لأن المنزل – مزودٌ بمكيفات مركزية (بمعنى أن مروحة المكيف على سطح المنزل) وفي المطبخ وكل حمام مروحةُ شفط تعمل عادة طوال الوقت.

– توجد خمسة أجنحة عائلية في – الدور العلوي ، مما يعني أن الدرج هو الأقل استخدامًا من حيث الوقت (فلا أحد يجلس على الدرج) والأكثر استخدامًا ف- في ذات الوقت لأن كل فرد في المنزل سيستخدم السلالم عدة مرات في اليوم ، باستثناء الشخص الذي يعيش في غرفة النوم – بالدور السفلي. على سبيل المثال ، قد لا تدخل المرأة التي لا تطبخ إلى المطبخ كل يوم وقد لا يكون لدى الرجل سبباً لدخول الصالة – لأسبوع -.

3) Example of family suite

A door to the hallway which leads to a suite with a bathroom and two rooms is a very common floor plan in Dhofar; sometimes there is an additional store room. When a couple is newly married, one room is a bedroom and the other a sitting room. If they have several children, the suite will be set up as above, with one room for the parents and one for the children. When the children are older, they might be moved into a different suite which has one room with same gender relatives of the same age (siblings, cousins, etc.) and the second room as a study/ plan room. Only in very large houses would one person have a suite to themselves.

3) – نموذجٌ لجناح عائلي

يعد تخطيط باب – الردهة – المؤدي إلى جناح – مكوَّنٍ من حمام وغرفتين تخطيطاً شائعاً جدًا في ظفار ؛ وقد تكون هناكَ أحياناً -غرفة تخزين إضافية. عندما يتزوج شخصان حديثًا ، تكون إحدى الغرف غرفة نوم والأخرى غرفة جلوس. – وإن كان – للزوجين عدة أطفال ، فسيتم إعداد الجناح على النحو التالي ، – غرفة واحدة للوالدين وغرفة للأطفال. عندما يكبر الأطفال ، قد – ينقلوا إلى جناح مختلف – – فيه غرفة – يشاطرونها أقاربهم من نفس الجنس – والعمر (الأشقاء وأبناء العم ، وما إلى ذلك) – وغرفة – ثانية تُستخدمُ كغرفة دراسة أو تحضير. ولن تجدَ شخصاً يسكنُ جناحاً بأكمله إلا – في المنازل – الضخمة.

I am very grateful to Arooba Al Mashikhi for her work in translating some of my essays about houses in Dhofar.

click here to see original post: July 10, 2021

Upper-class, English, Victorian-era homes had a set of rooms for children which would include a day nursery, night nursery, schoolroom, bathroom and the nanny’s room. In present-day America, a middle-class child might play on the kitchen floor while a parent is cooking, do homework on the dining room table, watch TV in a basement rec room, sit by the fire in a den or study, i.e. sit in different rooms for different purposes during one day.

كانت منازل الطبقة العليا الإنجليزية في العصر الفيكتوري تحتوي على مجموعة من الغرف للأطفال والتي تشمل حضانة نهارية وحضانة ليلية ، وغرفة مدرسية ، وحمام وغرفة للمربية. أما الان في أمريكا ، قد يلعب طفل من الطبقة المتوسطة على أرضية المطبخ أثناء قيام أحد الوالدين بالطهي أو أداء واجباته المنزلية على طاولة غرفة الطعام أو مشاهدة التلفزيون في غرفة الاسترخاء في الطابق السفلي ، أو الجلوس أو الدراسة بجانب الموقد في غرفة الطعام أي الجلوس في غرف مختلفة لأغراض مختلفة خلال يوم واحد.

Whereas young Dhofari children spend most of their in-door time in their parent’s bedroom and the salle. When they are close to puberty they will move to their own bedroom or a room with several children who are the same gender and around the same age. Children are only in the majlis in the presence of adults and for a reason, for example an uncle is visiting or they are working with a tutor.

في حين أن الأطفال في ظفار يقضون معظم وقتهم في المنزل في غرفة نوم والديهم وفي الصالة. عندما يقتربون من سن البلوغ ، ينتقلون إلى غرفة نومهم الخاصة أو غرفة بها العديد من الأطفال من نفس الجنس وفي نفس العمر تقريبًا. يتواجد الأطفال في المجلس فقط بحضور الكبار ولسبب ما ، على سبيل المثال ، عندما يقوم العم أو الخال بزيارة أو عند دراستهم مع معلمهم.

Dhofari children spend a lot of their free time out of the house once they can walk: in the hosh if younger than 3 or 4, then in front/ near house, then within the neighborhood in mixed gender/ mixed age groups until close to puberty. They also know the salle or majlis of many houses (grandparents, uncles/ aunts and older siblings) but will usually not play/ hang out in a cousin’s bedroom, although they might sleep there if it is an overnight visit. Children sleeping over at relatives’ houses is common, even among families which live close to each other. For example, when one female Dhofari friend was sick, she sent her child to stay for two weeks with her parents who live nearby.

يقضي الأطفال في ظفار الكثير من أوقات فراغهم خارج المنزل بمجرد أن يتمكنوا من المشي: في الحوش إذا كان أصغر من 3 أو 4 سنوات ، ثم أمام أو بالقرب المنزل ، ثم داخل الحي في مجموعات مختلطة الجنس والأعمار حتى قرب سن البلوغ . إنهم يعرفون أيضًا الصالة أو المجلس للعديد من المنازل (الأجداد والأعمام / العمات والأشقاء الأكبر سنًا) ولكنهم عادة لا يلعبون أو يتسكعون في غرفة نوم ابن عمهم ، على الرغم من أنهم قد ينامون هناك لليوم التالي إذا كانت زيارة ليلية. إن نوم الأطفال في منازل الأقارب أمر شائع ، حتى بين العائلات التي تعيش بالقرب من بعضها البعض. على سبيل المثال ، عندما كانت صديقة ظفارية مريضة ، أرسلت طفلها للإقامة لمدة أسبوعين مع والديها اللذين يعيشان في مكان قريب.

As children grow older, they experience the same house differently as the use of rooms is linked to both gender and age. For example, a Gibali girl visiting her paternal uncle’s house: as a baby she might be taken into the majlis by her father who is holding her; as a five-year old, she might spend the visit playing outside with male and female cousins; as a 14 year old, she might sit in the salle with her mom and older sisters. If she marries a cousin from this family, she will be expected to go into the majlis when there are visitors to bring tea and, perhaps, sit and visit.

مع تقدم الأطفال في العمر ، يعيشون في نفس المنزل بشكل مختلف حيث يرتبط استخدام الغرف بكل من الجنس والعمر. فعلى سبيل المثال ، عند زيارة فتاة جبالية منزل عمها: كطفلة قد يمسك والدها يدها ويحملها إلى المجلس ؛ وعندما تبلغ من العمر خمس سنوات ، قد تقضي الزيارة تلعب في الخارج مع أبناء عمومتها من الذكور والإناث ؛ وعندما تبلغ من العمر 14 عامًا ، قد تجلس في الصالة مع والدتها وأخواتها الأكبر سنًا. وإذا تزوجت من ابن عم من هذه العائلة ، فمن المتوقع أن تذهب إلى المجلس عندما يكون هناك زوار لإحضار الشاي ، وربما للجلوس والزيارة.

Further, men experience houses differently according to what his relationship is with the house owners. A boy will spend time in the salle of relatives’ houses when young and the majlis when older but there are many variables. For example, a 25-year-old Gibali man with three sisters (A, B and C) would have different visiting patterns depending on who owns/ controls the house that the sister lives in. He visits sister A in her salle because A and her husband own their own home and visits sister B in her salle because B married a cousin, thus the other women in the salle are his relatives. But he visits sister C in the majlis because C lives in her husband’s father’s home who are not relatives, so the salle is for C’s mother- and sisters-in-law.

فضلا عن ذلك، يستشعر الرجل المنازل بشكل مختلف وفقًا لعلاقته مع أصحاب المنزل، حيث يقضي الصبي وقتًا في الصالة بمنزل الأقارب عندما يكون صغيراً وفي المجلس عندما يكبر ولكن هناك متغيرات كثيرة. فعلى سبيل المثال ، سيكون لرجل جبالي يبلغ من العمر 25 عامًا ولديه ثلاث أخوات (أ ، ب ، ج) أنماط زيارة مختلفة اعتمادًا على من يملك / يتحكم في المنزل الذي تعيش فيه الأخت. فيزور الأخت (أ) في صالتها لأنها هي وزوجها يمتلكون منزلهما الخاص بهما ويزور الأخت “ب” في صالتها لأن “ب” تزوجت من ابن عمها ، فباقي النساء في الصالة هم من أقاربه. ولكنه يزور الأخت (ج) في المجلس لأن (ج) تعيش في منزل والد زوجها وهم ليسوا أقارب ، لذلك فإن الصالة مخصصة لوالدة زوجها وأخواته.

In a similar way, a married man who visits his wife when she is at her parent’s house might sit in the salle (if he is closely related to her family) or the majlis (if he is not). As most Dhofari women stay with their mother or an older sister for 40 days after the birth of their first child, a husband’s behavior is on display. All the female relatives of the new mother will know how often he visits, how long he stays and what he brings with him. This information is passed on to the general community, for example when a general question such as “how is the new mom doing?” is answered with, “fine, alhamdulillah, and her husband came every day to visit in the majlis,” his reputation (and the reputation of his family) is increased. This is a man who respects his wife and takes his responsibilities seriously. When the sister of one friend had her first baby, the family tried not to use the majlis at certain times so the husband could visit his wife and baby in privacy.

وبطريقة مماثلة ، يمكن للرجل المتزوج الذي يزور زوجته عندما تكون في منزل والديها أن يجلس في الصالة (إذا كان على صلة وثيقة بأسرتها) أو في المجلس (إذا لم يكن كذلك). ونظرًا لأن معظم النساء الظفاريات يبقين مع أمهن أو أختهن الكبرى لمدة 40 يومًا بعد ولادة طفلهن الأول ، فإن سلوك الزوج يكون على مرأى من الجميع. فستعرف جميع قريبات الأم الجديدة عدد المرات التي يزورها ، ومدة إقامته وما الذي يجلبه معه عند الزيارة. وتنقل هذه المعلومات إلى المجتمع العام ، فعلى سبيل المثال عند طرح سؤال عام مثل “كيف حال الأم الجديدة؟” تكون الإجابة: “بخير ، الحمد لله ، وزوجها يأتي كل يوم لزيارتها في المجلس” ، فتزداد شهرته (وسمعة عائلته). فهذا رجل يحترم زوجته ويأخذ مسؤولياته على محمل الجد. وعندما رزقت أخت أحد الأصدقاء بمولودها الأول ، حاولت الأسرة عدم استخدام المجلس في أوقات معينة حتى يتمكن الزوج من زيارة زوجته وطفله في خصوصية.

(photo of majlis by informant, used with permission)

(صورة للمجلس التقطها أحد مقدمي المعلومات، وعرضت بعد الموافقة)

“Explorations in the North-west Indian Ocean: The Research Journeys of the ‘Palinurus’ along the Omani Coast in the mid-1800s.”

Research Expeditions to India and the Indian Ocean in Early Modern and Modern Times, sponsored by the German Maritime Museum / Leibniz Institute for Maritime History. Nov. 3 and 4, 2022.

I am grateful that Salim Al Almri has given me permission to post these lovely photos of animals in the Dhofar region.

Camels

Gazelles

Ibex (Wael)

The Arabic Alphabet: A Guided Tour – http://alifbatourguide.com/

by Michael Beard, illustrated by Houman Mortazavi

“Shin is for Saracen” – http://alifbatourguide.com/the-arabic-alphabet/shin/

excerpt:

Shîn is distinguished from Sîn by a triangle of dots over the teeth (as with Tha or Z͎ha). To my ear it makes sense that the Sh sound would be represented like an S with something added. Shîn sounds heavier, thicker, as if it utilized more of the voice-making apparatus. Arabic adds the three dots to Sin (as we add the letter H next to the letter S).

In manuscripts of sufficient age you will also see the clearer sibilant Sîn carrying the same three-dot load, but underneath, i.e., ڛ, (no doubt to make the difference between Sîn and Shîn unmistakable). In contemporary Turkish (in Roman letters), the SH sound is represented by ş, an S with a cedilla, as in şaşmak, to be surprised, or şişlemek, to pierce to stab, or şiş, a skewer, as in şişkebap.

Spring

The great Greek poet Constantine Cavafy lived in Alexandria. He knew enough Arabic to entitle one of his early poems (1890s), «Σαμ ελ Νεσíμ» (Sam el Nesîm), the name of an Egyptian spring festival. Or almost the name, since the festival is properly speaking Shamm al-nasîm, with a Shîn. You cannot blame him, as there is no SH sound in Greek.

Shamma in Arabic means to sniff or breathe in. Shamm al-Nasim means “inhaling the air,” “enjoying the air,” to greet the coming of spring. It can be traced back, before Arabic, to a word with a similar sound, in ancient Egyptian, a proper noun Shemu, the season between May and September. Shamm al-Nasîm is observed by both Christians and Muslims according to the Coptic calendar, the day after Coptic Easter. Edward Lane, writing in 1834, translates shamm al-nasim “smelling of the Z͎ephyr”: “the citizens of Cairo ride or walk a little way into the country, or go in boats, generally northwards to take the air… The greater number dine in the country or on the river” (Lane, 483). It is, Lane adds, a festival observed with persistence: “This year (1834) they were treated with a violent hot wind, accompanied by clouds of dust, instead of the neseem; but considerable numbers, notwithstanding, went out to ‘smell’ it.”

Cavafy didn’t keep “Sam el Nesîm” in his complete works, perhaps because the premise is too simple. (It’s a poem which says this is a time of celebration, but down deep we know we’ll return to our usual grim lives soon enough. Or, more personally, “it’s their celebration, not mine.”) There are many ways to describe the grain of daily life in a culture other than ours; you can’t help but suspect that even in the most neutral descriptions there is something suspicious or demeaning. If Cavafy knew the etymology, as is likely enough, it would have been possible to make more use of the fact that the contemporary festivals traced back pre-Islamic sources. Poets (شعراء, shu‘râ’) love that.

You must be logged in to post a comment.