I think of Dhofari houses as the antithesis of expensive Victorian-era houses with all those little rooms with separate purposes: the morning room, the seamstress’ room, billiard room, the music room, the library etc. In Dhofari houses, there are usually only four types of rooms: sitting room, bedroom, kitchen and bathroom. The first three types are furnished with the same pattern of empty space in the middle: the majlis/ salle with stuffed chairs and sofas around the walls with coffee tables next to them and an open space in the middle; the bedroom with the bed and cupboards/ dressers against the walls and open space in the middle of the room and kitchens with counters set around the walls. Furthermore, all rooms are built square or rectangular; there are no nooks or closets. Books, dishes, clothes, beddings, etc. are stored in pieces of furniture that are placed next to a wall. Dining and kitchen tables are placed close to one wall or where two walls meet. To look at this from a child’s perspective, while playing hide-and-go-seek, kids can’t hide in closets or behind furniture. The only places to hide are behind doors or inside kitchen cabinets/ bedroom clothes cupboards.

The effect of this pattern in that when you walk into a room, you can see everyone and everything immediately. I believe the reason for this pattern is that when Gibalis sit together, they always try to keep everyone in the group in view. Men sitting on sofas placed next to the walls in a majlis are a mirror image of men sitting on a mat near a fire for a picnic. One way to keep a more rounded shape in a square or rectangular room is that instead of sectional sofas meeting at a 90 corner angles, either the corner section is angled, or an arm rest is placed at the corner (see examples below).

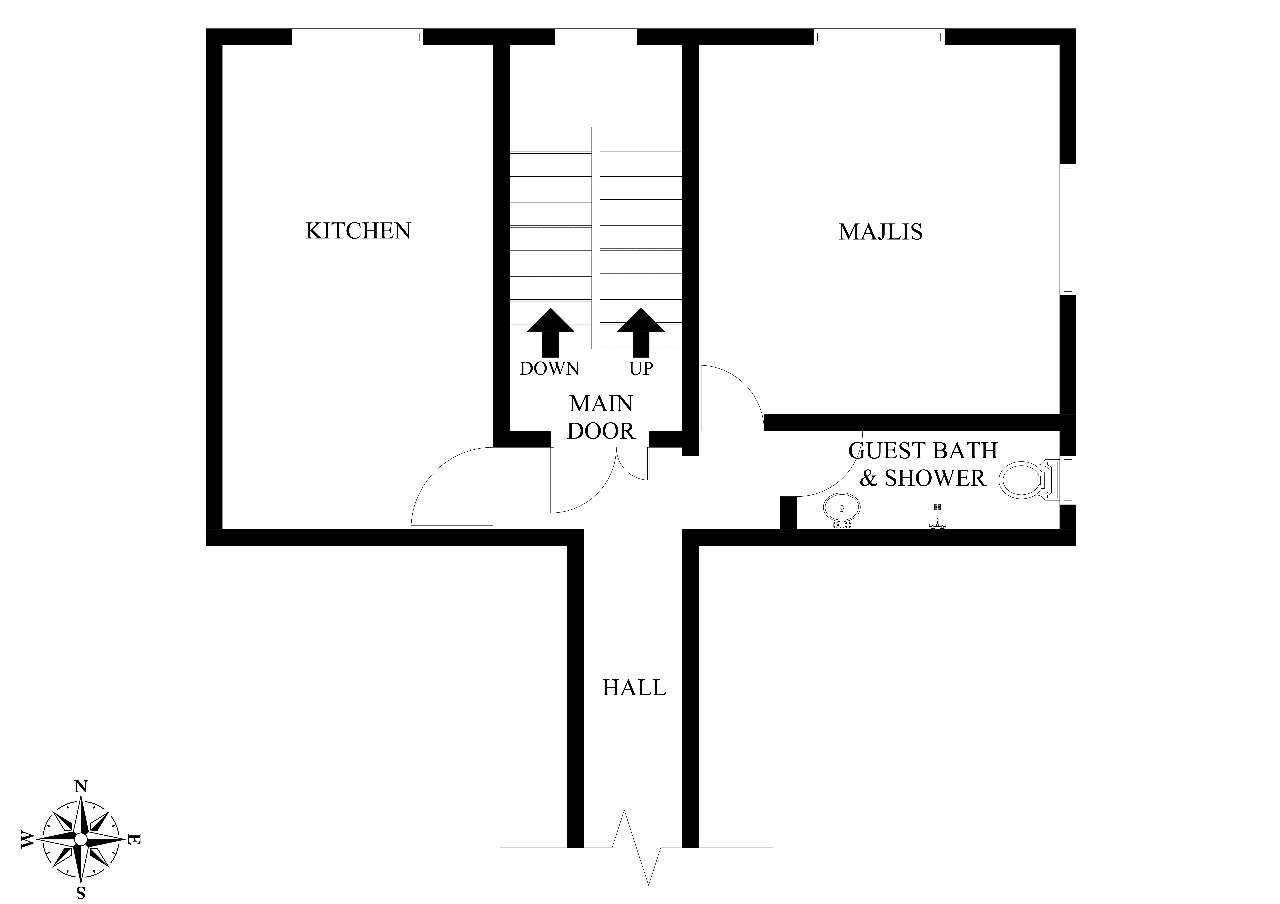

Further, hallways in Dhofar are much wider than the arm span. Thus, although houses aren’t built ‘open plan,’ from certain vantage points, you can see many different spaces. Standing in the main ground-floor hallway, one can usually see the front door, the entrance to the kitchen, the main stairs and into the salle. From the top of the stairs one can usually see down to the main ground-floor hallway, the open space (sometimes used as a salle) at the top of the stairs and the doors to most or all of the first-floor bedrooms.

A North American house might have a “great room” with a combined kitchen, dining area and sitting area, but normally this is not in sight of the front door. Whereas in a Dhofari house, an older female relative who sits in the salle will see every person who comes in or leaves unless they leave by the kitchen door.

Another way to think about types of rooms is to consider that many middle- and upper-class North American homes have rooms for work, relaxation and/ or exercise such as a home office, craft room, gym, yoga studio. etc. which might be the former bedroom of a child who has moved out. There is a standard trope of a child going to college and his/ her room ‘disappears’ as it has been entirely repurposed.

Whereas in Dhofar, while the people who stay in a room might change, the purpose seldom does. For example, three boys might share a bedroom on the ground floor. In time, an additional story is added and two boys move to an upstairs bedroom while the original room is redone for the oldest boy and his bride. After this couple have a few children, they move to a suite on the first floor and the room is refurbished for a grandparent who cannot manage to walk up stairs.

One consequence of these building and furnishing conventions is that for some Dhofaris, “privacy” refers to their personal thoughts and emotions as they are almost always in actual or potential sight of other people when in a house. Privacy might never be found in a bedroom as children might share a room (once close to puberty, in single gender groups) and young children stay with their parents.

Another consequence is the Dhofari ability to have secret conversations in front of other people. In American families, there can be family-only codes such as saying, “FHB” (family hold back) at a party, meaning there might not be enough food so family should eat less so the guests can have as much as they want. Or an older person raising their eyebrows, opening their eyes widely and staring at a person to show dissatisfaction with inappropriate behavior but it is more common for family members simply to make verbal requests/ demands in front of visitors.

In Dhofar, having a large salle with a perfect view of every person combined with the need to always show a calm and positive expression means it more usual for older relatives to direct younger people with quick eye movements (such as looking at the AC unit to tell someone to make the room cooler) or hand gestures. When I taught a class on culture and asked students to come up with examples of non-verbal communication, many explained the signals for “bring fresh tea” and “bring more food” that older siblings and parents used. Several times at weddings, I have sat next to a woman who was part of the hosting family and a sister would come over to, almost inaudibly, ask a question or give information. The two would discuss hosting emergencies (not enough food, the bride will arrive very late, etc.) with no visible sign of agitation so that the dozens of women who could see them have no idea that there is a problem.

A note on bathrooms: Bathrooms are almost always ‘dead-end.’ I have seen only one example of a ‘pass-through’ bathroom with two entrances in a house built before 2000. They are usually rectangular and built with the narrow end on an outside wall or lightwell to allow for the window and extractor fan. They are usually set up with an open design (e.g. no interior walls such as a low partition to screen the toilet) with a pedestal sink or sink on a counter with empty space beneath and a shelving unit next to the wall. The sink is always closest to the door. The shower area usually does not have a curtain and is marked off with a slightly lowered floor with a drain. Some have tiled steps along one side. Bathtubs are rare; if there is one, it usually has a seat. The steps and seat are for the ritual washing before prayers during which face, hands and feet must be cleaned.

The door to a guest bathroom that is attached to or near the majlis and salle often opens to a space with one or more sinks, then another inner door leads to a small room with a toilet, shower and sink so that guests might wash their hands while the toilet/ shower room is in use. (see example below)

Bathrooms in the family/ private area of the house are built open-plan for one person to use at a time, unless it is a parent helping a small child (see example below). Some North American bathrooms are set up with the toilet half-hidden behind a low wall and shower curtains so that two people might use the room at the same time but I have not heard of that in Dhofar.

examples of majlis/ salle designed to create circular seating pattern in square room

examples of bathrooms

You must be logged in to post a comment.